Colleagues, not Clones: Remembering Bob Paynter (1949-2023)

Bob Paynter was my friend, my dissertation advisor, and perhaps my most important intellectual and political mentor. He died Sunday, after a long illness.

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter at the Frary House-Barnard Tavern field school, Deerfield, Massachusetts, Summer 2007 |

I first heard of Bob through Paul Mullins who himself died only a few weeks ago. Paul had studied at UMass Amherst, and Bob, a professor there from 1981 until his retirement in 2016, had been his dissertation advisor and collaborator. I was still a wayward undergraduate at Boston University. I had found archaeology, and loved the promise of its rich exploration of the everyday material past, but had almost no teachers and mentors with whom I felt comfortable. Mary Beaudry, who died in 2020 was the exception. I also wasn’t completely sure that I wanted or needed a PhD; inspired by the growth of public and community archaeology, I was envisioning a path that involved a master’s degree and some kind of public-facing heritage-work (which, is, somewhat ironically, where I ended up)

All the same, I convinced a friend with a car to drive me out to UMass to meet with Bob. We met in his office, which was piled with books, papers, and the delightful ephemera of a rich career. At the time I met him, he was already well into the major intellectual and scholarly projects that would define him–the exploration of race and racism in supposedly “White” rural Massachusetts, the politics of narrative as a form of explanation about the past, the relationship of landscape changes to global structural forces like capitalism, and the complexities of indigenous recognition and repatriation.

Of course, I didn’t know any of this when I sat down with this jovial, bearded guy, whose warm and friendly demeanor immediately disarmed my anxieties about the whole endeavor. I told him then that I wasn’t sure about some other programs I had visited, in that it felt like I was walking into somebody’s castle to be anointed as a squire.

Bob told me something in that room that’s always stuck with me; that what he wanted as a graduate mentor was to make colleagues, not clones. He wanted people whose intellectual and scholarly development would grow archaeology, and that growth would in turn push him to grow. These words, and Bob’s infectious enthusiasm, convinced me to join the UMass anthropology community in the Fall of 2002. I would spend the next decade there. It’s where I met the love of my life, made lifelong friends, and grew an intellectual and professional garden that has only thrived and expanded since. All of this came from Bob’s welcoming and supportive model of education, and so much of how I would get to know Bob would be through the lens of someone who treated me as a colleague from the moment I stepped into his classroom in 2002.

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter with Stockbridge-Munsee Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Steve Comer, W.E.B. Du Bois Homesite, Great Barrington, MA, Summer 2003" |

This maybe a good time for an intellectual biography, at least as I came to learn it. Strap in!

Bob was an historical archaeologist, which is often glossed as the archaeological study of the spread of Europeans around the globe from the 15th-19th centuries, and which Bob referred to as the archaeology of colonization, capitalism, and conquest. Just that terminological difference should give a sense of his uniqueness and emphasis. At the time he was coming up, much of the sub-discipline was fairly descriptive rather than explanatory. James Deetz (with whom Bob had studied as an undergrad, and worked with as an interpreter at Plimoth Plantation) had intervened in this by bringing structuralist theory into the interpretation of early Euro-American material culture, but as Bob would later write, structuralism brought with it its own problems of understanding difference and inequality in the past. In short, Bob questioned whether changing cultural mind-sets and their congruence with the diffusion of stylistic traits in material things could help one understand the impact of the conquest of indigenous people, the violence of chattel slavery, or the class inequalities that were present in the earliest colonies. Another framework was necessary.

At the same time, Bob had protested the Vietnam war and been a student of the civil rights movement. The unstable and radical politics of the time saturated his thinking, and he brought that commitment to foregrounding politics into his archaeological work. Marxism was the theoretical framework he ultimately adopted, though he was never doctrinaire about what that meant–he usually referred to himself as a “Groucho Marxist”. His biggest influences came from scholars who brought Marxism to bear on other disciplines, particulary Eric Wolf and his masterful synthesis of anthropology and modes of production in “Europe and the People Without History”, or David Harvey’s close reading of the geography and spatiality of capitalism through a Marxist lens begun in “Social Justice and the City” and “The Limits to Capital”. Bob ’s early work, trying to locate seemingly isolated and bucolic rural New England into the capitalist world system, was an attempt to graft archaeological analysis of settlement patterns and landscapes into Marx’s insights about capitalist development and contradictions.

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter excavating at the Frary House-Barnard Tavern in Deerfield, Summer 2005 |

But plugged into this class-focused Marxism was an abiding interest in race and African-American life. Not long after he started at UMass, a couple of professors from the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of African-American Studies wandered over with a box full of objects they had collected from the surface of “The House of the Black Burghardts” in Great Barrington, MA, the boyhood home of the legendary scholar and statesman W.E.B. Du Bois. This brief interaction began a decades long engagement with Du Bois, intellectually and historically. Bob ran archaeological field schools at the Du Bois site in 1983, 1984, and again in 2003 (where I served in my first teaching position as a very green Lab and Education Coordinator). Bob was also profoundly influenced by Du Bois’s astonishing career and scholarship, and wrote important articles about Du Bois and archaeology, and about race and archaeology more generally.

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter talking to the Great Barrington community at the AME Zion Church about the Archaeology of the W.E.B. Du Bois homesite. On the far right is Du Bois’s adopted son David, who had just finished speaking. Summer 2003 |

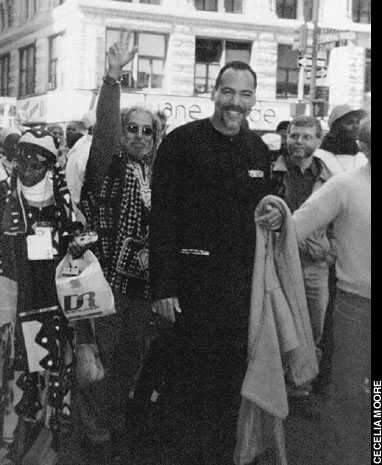

And he was immensely supportive of African-American students in archaeology and anthropology. Two of his graduate advisees, Warren Perry and Michael Blakey, co-directed the African Burial Ground Project in New York City, arguably the most important public archaeology project of the the last 30 years, and while Bob wasn’t directly involved, his assertion that both the violent history and vibrant achievements of African-Americans deserved prominence in the past and the present sat at the heart of that project. Bob marched with Warren and Michael, along with thousands of others, down Broadway during the ancestor reburial of 2003.

|

|---|

| The crowd of thousands, including Warren Perry, Michael Blakey, and Bob Paynter, marching down Broadway for the ancestor reburial of the African-Burial Ground in 2003. Image courtesy of Cecelia Moore |

Overall, Bob spent his career interrogating inequality in the past and the present. He wrote about the labor exploitation in cultural resource management archaeology, the state of research in the origins and durability of inequality in the distant and recent past, and the political implications of different kinds of historical narratives. He also combined this scholarly commitment with support for historically marginalized groups. He worked tirelessly helping UMass and the Five Colleges in a difficult and messy repatriation of Indigenous human remains, even when this involved Indigenous groups who were not federally recognized.

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter and Students listening to Afro-Cherokee scholar Ron Welburn, ca. 2005 |

What made Bob so special is that he was committed to making sure that his students didn’t memorize his accomplishments and interests to succeed (though, as you can see from my post, many of us did!) He truly lived out the words that he said to me in his cluttered office that spring in 2002 to try and become his colleague–no easy task. Even as I worked on various archaeology projects in Historic Deerfield, a place he spent a lot of research time, he always encouraged me to bring my own perspective and spin on things, and to push beyond what he had done.

|

|---|

| Bob and his Colleagues, some of whom started as students ca. 2020. Top: Martin Wobst, Jim Delle, Claire Carlson, Randy McGuire, Warren Perry, Jim Moore, Whitney Battle-Baptiste, Jonathan Hill, Broughton Anderson, Steve Lacy, Anthony Martin, Paul Mullins. Bottom: Mike Nassaney, Bob Paynter, Tom Patterson |

And he did this even as he was a rich and charismatic teacher in his own right. Year after year, he taught Introduction to Anthropology, a course that was specifically designed for non-majors to fulfil general education requirements. But rather than seeing this as a chore or an extraneous task, Bob relished the opportunity to teach people what Anthropology has learned about the world–that human cultural variation is vast but understandable, that human biological variation is minimal and the taken-for-granted categories we frequently rely on (especially race) are fictions either convenient or malevolent, and finally that culture, which we make together, is an adaptive niche unto itself. His lectures in that course were enthusiastic, humorous, and provocative. I have ripped off, almost whole-cloth, his lecture on the origins of Christmas in that class, boisterous singing and all.

So many of the beautiful memories I have of him grew out of this fundamental interpersonal ethic–that anyone you meet has the potential to teach you, and thereby to change you. I remember joyful conversations in his office, his car on a welcome ride home, in his backyard, trading new discoveries in fiction (he and I both loved science-fiction and fantasy) or music (he was a lifelong fan of Jazz and a trumpet player of some skill) or the day-to-day of US politics (we spent a cold but wonderful afternoon driving New Hampshire voters to the polls in November of 2008).

And now he’s gone, and all of us who studied with him, worked with him, talked with him, argued with him; all of us have to learn how to live up to the standard that he set, to become the colleagues he always believed and supported us to be.

To think and live as though the past is not something gone, but alive and potent in everything we do, and any future we may make

To center politics, struggle and questions of inequality in any scholarly or intellectual endeavor

To refuse dogma in favor of curiosity and the possibility of explanation

To treat everyone around us as a potential teacher

I’m going to miss my friend so very much. I’ll miss his spirit, his sharp and clever mind, his support, and his exuberant laugh.

Rest in peace and in power, Bob Paynter

|

|---|

| Bob Paynter (right) treating me (green hat), and two undergraduate field school students as colleagues, Deerfield, summer 2005 |