Booknotes: The Runaway Restaurant by Tessa Yang

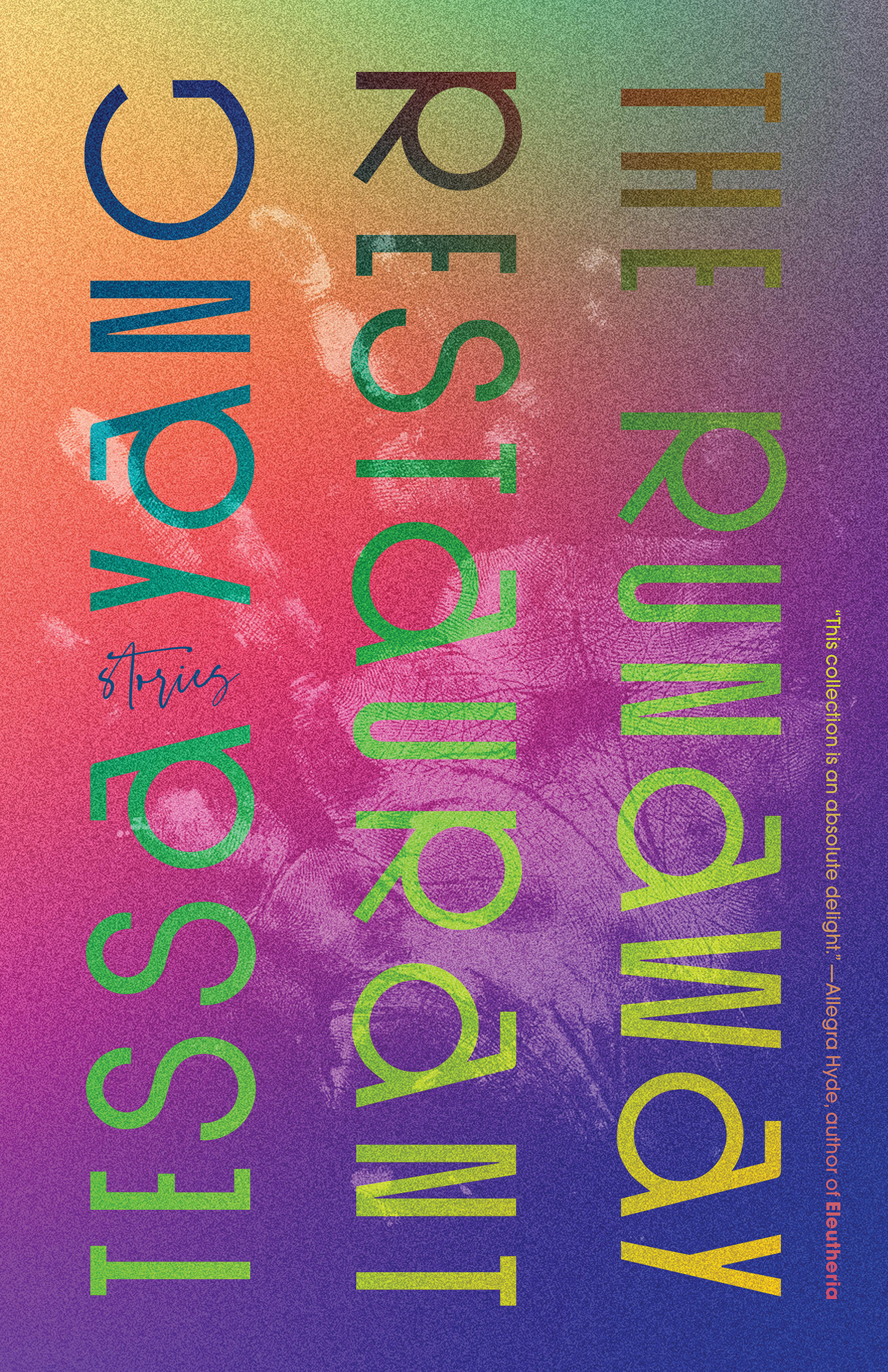

The Runaway Restaurant

by Tessa Yang

Finished 8/20/22

A rich and evocative collection of fantastical short stories that explore the ambiguous edges of relationships and identity.

The stories in this collection deploy many familiar concepts or imagery from fantastic fiction: futuristic technology, witchcraft, ghosts, apocalypse. But these commonplace devices provide a vantage point through which Yang explores the difficult and uneven terrain of close relationships; the lines that run between lovers, parents and children, or seemingly inseparable friends. One of the common themes that lurks in these stories is that natural or supernatural limits force us to reckon with who we are to ourselves, and to others. In “Others Like You”, a coven of witches are drawn to an eastern seaboard tourist town, only to find themselves mystically trapped there, and stewing in their own interpersonal frustrations as much as in their own power. In “Runners”, two newly parentless teenage cousins begin to invade the empty homes of their neighbors, trying on new identities from the mundane trinkets they steal, but increasingly hemmed in by the tensions and contradictions of their unstated competition and the echoes of their relationships to their missing relatives. Yang’s characters learn who they are and what they want through the walls they build, or that are built for them by forces either interpersonal or alien.

Yang’s prose is rich but unpretentious. One character ponders “the unsolvable riddle of love and resentment that have curdled until one is indistinguishable from the other”. Another woman, recently deceased, describes her ghostly body as “a sensation like double doors bursting open, admitting air and light and music into the shuttered room she’d become during those final, wretched days.” Yang is clearly delighted by the weird situations in which she plots her characters, but her most delicate and thoughtful exposition comes in probing who her characters are, how they feel, and what they want.

As an archaeologist, I was intrigued by the evocations of material things that are scattered throughout this collection. Many of these stories revolve around the secret meanings of simple or anonymous objects. A worn and well-used college dorm room wardrobe periodically emanates maple leaves. Abandoned cars left in an old barn give meaning and purpose to the ghosts that haunt it. “Wonder in her Wake”, my favorite story in the collection, follows a hoarding mother and son who collect refuse and ultimately reconfigure it into magic. This latter is a subtly (or even explicitly) Lovecraftian story, where every character, in their own way, seems to be seeking some forbidden or mysterious knowledge.

It’s really delightful when your friends make wonderful art. I was given an advance copy of this book by the author in exchange for an honest review. Knowing Tessa, and having read her work before, I figured it would be good but it exceeded my already high expectations. This is a great collection, strange and heartfelt and insightful and wide-ranging. Fans of fantastic and speculative fiction will find that it treats old friends in new ways, and more literary-inclined readers will appreciate Yang’s subtlety, rich characterization, and inviting prose.