Booknotes: Making Mountains: New York City and the Catskills by David Stradling

Making Mountains: New York City and the Catskills

by

David Stradling

Finished 5/30/23

An insightful tour of the history, culture, and built environment of the Catskill mountains, showing how the region was co-constructed as a timeless and ancient wilderness alongside New York City’s metropolitan growth.

Building on the tradition of environmental history laid out by William Cronon, as well as the rich dialectical analysis of Raymond Williams' “The Country and the City”, Stradling explores what Washington Irving would call “the great poetical region of our country”, and how the image of the rural catskills lined up with the lived reality and built environment of the place. Not surprisingly, he finds that much of the history of the Catskills since it was settled by Euro-Americans after the Revolutionary war is a history of the City shaping the countryside, and being, in turn, shaped by the the countryside. New York City could not exist without the Catskills. The clean water for which the city was justly hailed for much of the 20th century came from Catksill reservoirs that destroyed whole valleys of villages. The stones that built many of the cities iconic structures and paved its roads were minded in Catskill quarries. Most importantly, the image of Catskills as a wild, unspoiled wilderness provided a magnetic pull to city tourists seeking to escape crowded urban 19th and 20th century life. But this image was, of course, contrived; from the moment the Catskills was settled by Europeans and Americans, it was sketched in literature and in art as a place of deep history, wild nature, and romantically ruined (or empty) habitation.

Chapter 1 focuses on how the earliest American residents made a living in the Catskills. While Mohican, Haudenosaunee, and Lenne Lenape peoples had lived in the region since time immemorial, by the American Revolution, they had largely fled to safer environs, and Americans, seeking land for agriculture, moved in. Like many hilly farms in other regions, Catskills farmers generally produced a range of products based largely on pasturage, as row crops were difficult given the terrain. They were quite diversified, raising a variety of products for local exchange, and a few key products for sale in urban markets. Stradling notes that the major products of the Catskills were often not strictly agricultural, but consisted of non-edible biotic materials like timber, tanned leather, and eventually bluestone, which served as New York City’s sidewalk paving for much of the 19th century. However, the reliance on urban markets linked Catskill farmers to the boom and bust cycles of 19th century capitalism, and many farms failed. Ironically, it was this failure that created one of the key images associated with the Catskills in the minds of tourists: the ruin, which fed into romantic notions of the region as a site of struggle between culture and nature. As Stradling notes “urban visitors to the countryside, distanced from the rural struggle for success, could look fondly upon the ruins that evidenced failure, and think mostly how wonderful it must have been to live so close to nature” (45)

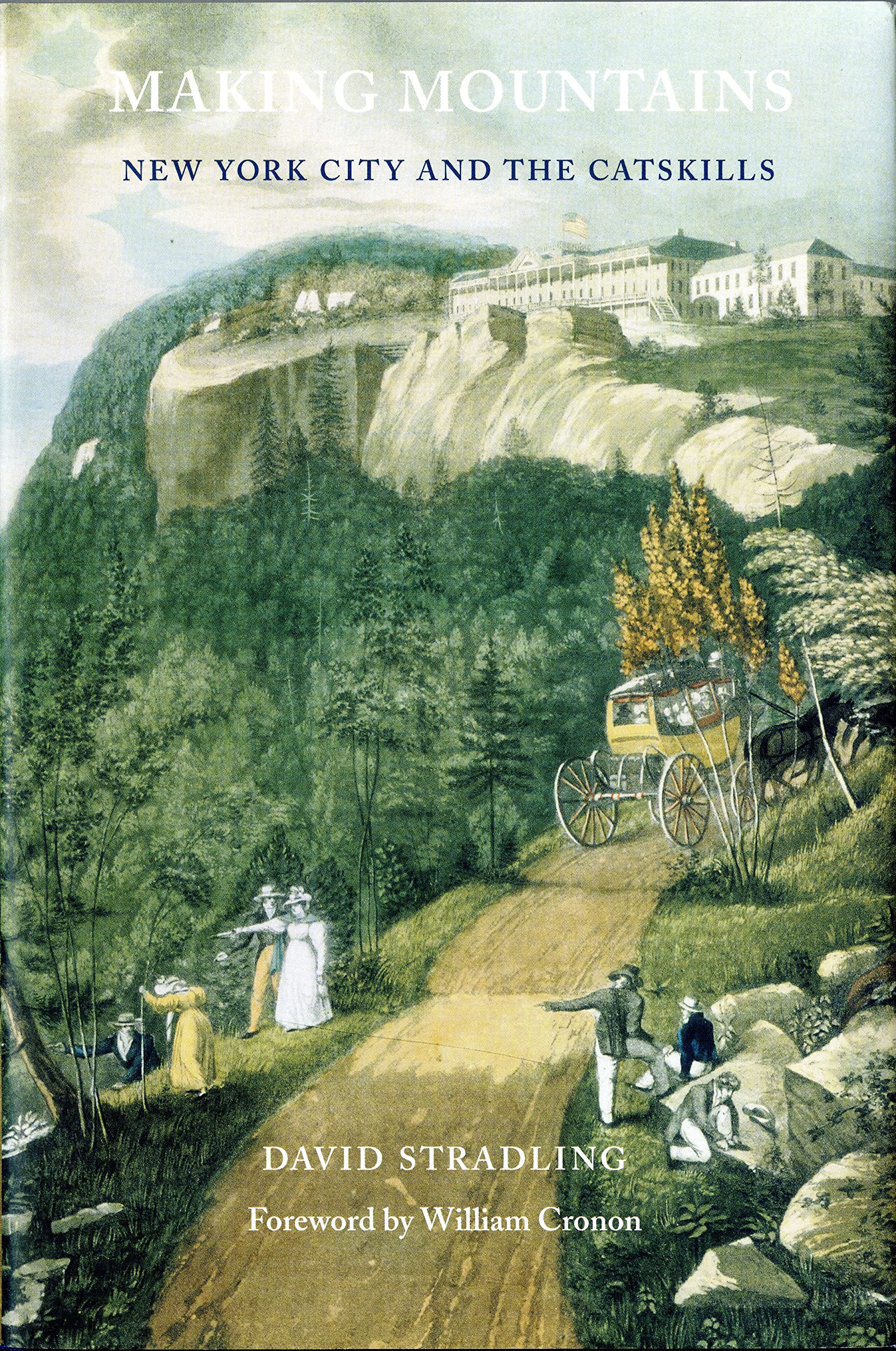

Chapter 2 begins to outline how this romanticism manifested in art and literature, creating a fictive past and romantic present for these mountains on which farmers continued to struggle. The key figures in this movement were Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, and Thomas Cole. Irving and Cooper highlighted the historicity of the Catskills, melding folklore, Dutch and English history, Native American life, and the environmental setting to create cultural association in the Catskills that would develop and persist to the present day. Irving, whose most famous Catskills creation was Rip Van Winkle, imbued the region with “instant lore–a deep history created in the imagination of a fiction writer.” (49) Cooper was born in Cooperstown, on the other side of the Mountains, but moved as a young man to Westchester county, from where he launched his writing career. His Natty Bumpo, depicted in “The Pioneers” was a character who stood for a decaying past, but also as a marker of “the mythical frontier hero” (51), which was easy for many 19th century Americans to embrace. Finally, Cole, and the Hudson River School of painters that he founded, embraced the Catskills as a place where one might encounter “The Sublime”. This mix of aesthetic and emotional feelings were part of the romantic tradition that saw the apprehension of nature (even in artistic depictions) as a moment of holy and meaningful engagement, and particularly for urban dwellers for whom the city was increasingly a place of difference, discord, and dirt.. Cole’s work, which drew on European landscape realism, but linked it to the American landscape of the Catskills, was always tied into the New York art market, and indeed, much of Cole’s early work was done in his New York City studio. Again, the country and the city cannot be meaningfully separated.

Chapter 3 looks out how this imagery of wilderness and history spurred the growth of tourism in the region. As early as 1828, local landmarks and buildings were being named after Rip Van Winkle, signaling that locals were making use of the imagery of the region to attract tourists. Initial tourists came as part of the American “grand tour” modeled on the middle class 18th century European version which included classical and medieval ruins. But for a variety of reasons, tours of American scenary and locales were dotted with hotels that catered to such visitors, and the Catskill Mountain House, opened in 1828, inaugurated this trend in the region. For visitors of lesser means, farmers opened up rooms for boarders, the income from which gradually supplanted agricultural income, eroding the urban-rural divide even further. Advertising and descriptions of the period continued to exemplify the notion of sublimity championed by Cole, and visitors could use the hotels to behold the power of nature and the wilderness, despite the wild landscape being somewhat contrived. For example, Kaaterskill Falls, one of the most popular destinations for viewing the sublime, was completely controlled over the course of the 19th century by a series of dams that would allow for waterflow at key visitor moments. The Catskills was already a cultural landscape even as tourists from New York City saw it more and more as an untouched wilderness.

Chapter 4 examines how the Catskills “wilderness” was structured and preserved, both through legislation, and through the private actions of individuals like fly-fishermen who used their wealth and status to maintain undeveloped lands for their own use. It also details the life and writings of naturalist John Burroughs, born in the Catskills and a steady but eccentric chronicler of life there. Key in this chapter is that state preservation laws understood that preservation was not exclusive; forests need trails and lookouts and other methods for regulating and structuring human usage. This was equally true for fly-fishers, a sport that grew in popularity at the end of the 19th century, especially among urban middle-class and elites, and for whom preservation of waters and stocking of fish were methods of organizing nature for their hobby and continued use. The nature of the Catskills “wilderness” was always one that linked the biotic and cultural worlds. The ambiguity emerged from how much of human activity to allow and who should be included or excluded. This chapter ends with a discussion of the beloved children’s book “My Side of the Mountain” by Jean Craighead George, which chronicles a young Brooklyn boy’s return to his family’s Catskills property where he lives in the wilderness. Coming to the untrammeled, natural countryside from the city remained an attractive fantasy for young and old alike, and the Catskills was a place where such fantasies could be enacted and their effects structured.

Chapter 5 documents the long and complicated process of how New York City’s water supply came to reside in the Catskills, and the changes that this wrought in the region. The construction of the Ashokan reservoir which flooded several Catskills towns, was the culmination of a complex political and cultural argument about the relationship of the country to the city. Even to this day, locals remain ambivalent or even hostile to the city’s extraction of water. And yet, as Stradling notes, the amount of land owned by New York City in the Catskills (as well as the tax revenue from such land) makes it a significant political and economic presence in the region.

Chapter 6 focuses on Catskill tourism in the 20th century, and particularly how urban Jewish tourism, in the region expanded during the middle decades of the century. Middle-class Jews from New York City’s often crowded ethnic enclaves found that the Catskills were a space of retreat and openness. The hospitality industries of the Catskills expanded to follow suit, creating, for much of the century, the Borscht Belt and its associated restaurants, hotels, and entertainment styles. It also provided an incubator for much of what became stand-up comedy, and Stradling notes a number of prominent entertainers who began as Borscht Belt comedians. It was the gradual inclusion of Jewish people into other aspects of American life and the cessation of outright antisemitic prejudice that saw the downfall of the Borscht Belt hotels, as Jews found that they had the resources to travel to other areas outside these particular tourist enclaves in Sullivan county.

Chapter 7 looks at how the long-time interconnectedness of the Catskills and the City culminated in the suburbanization of the Catskills with the expansion of roadways and the growth of automobile ownership in the 20th century. It also examines how counter-cultural forces from New York City in the latter half of the 20th century claimed the Catskills as their space, perhaps most dramatically at the Woodstock festival. This trend was part of a larger suburbanization of the Catskills, which made the region an attractive one for urban working car owners, but also exacerbated the problems of suburban development found in many large metropolitan areas of monotony and de-territorialization. At the same time, the heavy state investment in roads and highways meant that the Catskills became a region that tourists drove through but not to, putting pressure on the hospitality industry that had thrived when the railroads structured tourist movement in the region. All of this anxiety was accompanied, in the latter half of the century, by the growth of artist communities and counter-cultural forces in the region. Bob Dylan’s move to Woodstock (and his eventual retreat even further) is the most prominent exemplar here. But the chapter (and the book) ends with the contradictions that have plagued the region since it began; tensions between its cultural “rurality” and its urban reliance, between the past and the future, and between conservation and access.

I learned a ton from this book, and will likely dip back into it for insights both for my own life, and for teaching. At the same time, I have a couple of minor quibbles. The first has to do with Indigenous people’s broad absence from the book. Stradling indicates early on that Native people “did make use of the Mountains” (21) but that aside from place-names, evidence of Native American occupation has long since disappeared." But given the way that Native people are romanticized as being part of nature across the United States and Canada (and especially when they are seen as “vanishing” as they are in the 19th century), I think there’s a bigger story here. James Fenimore Cooper’s writings, which Stradling heavily quotes, are loaded with references to Native People, many of whom continued to live in and visit the region; John Brushell, who was the inspiration for Chinganchicook in Cooper’s “The Pioneers”, lived in Richfield Springs, just north of Cooperstown.

I also found myself thinking about the relationship between space and place, which Stradling (through his engagement with Raymond Williams) also investigates but somewhat blithely. An analysis that was grounded in, to follow Williams putting " ideas to the historical realities, at times to be confirmed, at times denied," would examine things like the historical settlement patterns of the Catksills, looking at who lived where, and who worked where, and when. Particuarly given that Stradling makes so much of the way that market integration linked Catskill farmers to boom and bust cycles, and that the ruins they left became fodder for cultural images of wilderness, I wanted to know more about the material realities of those boom and bust cycles. One great plug for archaeology is that it forces a confrontation with the material and the tangible. Stradling’s book would have benefited from such a richer engagement, something the archaeologist April Beisaw has been doing in her work on the archaeology and heritage of the Ashokan Reservoir displacements.

All in all, this was a fascinating and thought-provoking book about how rural and urban places get co-created, and how many of the same tensions that underly urban-rural dynamics in other parts of the world played out in the creation of the “timeless” “wild” “natural” Catskill mountains.